Abstract

Past research has suggested that the association between romantic relationship status (i.e., single vs. coupled) and well-being can be dependent on different aspects of an individual’s personal life. In the current research, we examined whether commitment readiness (i.e., the subjective sense that the current time is “right” to be in a committed romantic relationship) moderates the link between current relationship status and psychological well-being. With correlational data obtained from three independent samples (two from Singapore, one cross-cultural comparison between Singapore and USA), we found a significant moderating effect of commitment readiness. Coupled individuals higher in readiness reported greater levels of well-being than single individuals, whereas coupled individuals lower in readiness reported lower levels of well-being compared to their single counterparts. Implications regarding the role of commitment readiness in well-being are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Research on demographic trends in relationship status has indicated that more adults around the world are remaining single and are doing so for more years of their life (Himawan et al., 2017; Jones & Yeung, 2014; Milan, 2013; Simpson, 2016). This trend is particularly interesting given that research has long suggested that being single is associated with poorer well-being, an effect that has been replicated across many different studies (e.g., Haring-Hidore et al., 1985; Stronge et al., 2019) and nations (Diener et al., 1999). Nonetheless, the assumption that one needs to be in a romantic relationship to enjoy greater well-being has been challenged by various scholars (e.g., Conley et al., 2013), who argue that relationship status’s influences on well-being is dependent on various features of an individual’s life (Purol et al., 2021), such as relationship status satisfaction (Lehmann et al., 2015) and social approach-avoidance goals (Girme et al., 2016). These views imply that although relationship involvement tends to be beneficial, people show differences in the extent to which relationship status is associated with their well-being.

One important consideration is the recognition that people can vary in the degree to which they are receptive to involvement in a committed romantic relationship (Agnew et al., 2019; Hadden et al., 2018; Tan et al., 2020c). Indeed, a subjective perception of personal timing—whether the current time seems “right” to be involved in a relationship —appears to be consequential with respect to both the initial formation and continued maintenance of a relationship. When the time is considered “right”, one feels ready to pursue or maintain a close committed relationship. Importantly however, one person might feel exceptionally ready for a relationship but not be involved in one, whereas another person might not feel sufficiently ready for a relationship but is nevertheless currently involved in one. We posit that mismatches between one’s readiness to commit and actual relationship status may be associated with individual well-being.

1 Relationship Involvement and Well-being: Benefits and Costs

Prior research has alluded to the considerable influence of relationship status on one’s psychological well-being. Particularly, Erikson’s (1963, 1968) theory of psychosocial development posits that individuals learn to navigate various psychosocial “crises” specific to developmental life stages from infancy to adulthood, and the successful resolution of these challenges ultimately contribute to the formation of their personal identities and the fulfilment of their psychological needs (Maree, 2021). Importantly, individuals begin to engage in increased exploration of close relationships and develop a greater desire for commitment and intimacy with others during emerging adulthood (Maree, 2021). Close relationships help fulfil psychological needs of relatedness as well as affording a sense of security and trust within them (Ryan & Deci, 2001). Furthermore, given the primacy of romantic partnerships in support provision (Reis et al., 2000), close relationships are essential when coping with stress as well (McPherson et al., 2007; Lazarus & Folkman, 1984). Therefore, considering the intrinsic psychological desire for close relationships as well as the substantive benefits they confer, it is expected that one’s relationship status would likely be associated with psychological well-being.

This is corroborated by past research demonstrating that being coupled can indeed be positively associated with well-being (e.g., Dush & Amato, 2005; Stronge et al., 2019). This has been attributed, as least in part, to the provision of social and emotional resources from a romantic partner that can help to overcome challenges in life (Cohen, 2004), buffer stress (Tan & Tay, 2022), and augment positive outcomes (Gable et al., 2004). In contrast, single individuals potentially forgo such benefits to well-being (Soons & Liefbroer, 2008). Single people may be less likely to experience the fulfilment of relatedness needs (Baumeister & Leary, 1995; Deci & Ryan, 2000), poorer emotional well-being (Adamczyk & Segrin, 2015) and with negative effects on health and well-being (Holt-Lunstand et al., 2015). Moreover, remaining single for a longer duration may serve to accentuate the detrimental effects of singleness.

However, recent research has challenged the conclusion that coupled status provides unique well-being benefits (Lucas & Dyrenforth, 2005). For example, single individuals have reported greater levels of well-being than in previous years (Böger & Huxhold, 2020). This may be in part due to singles’ involvement in non-romantic relationships that serve to fulfil their intimacy, emotional and belongingness needs (e.g., Chopik, 2017), having higher-quality social networks (Kislev, 2021), as well as being able to pursue their individual interests and aspirations in a more unbridled fashion (DePaulo & Morris, 2005). Beyond the benefits of staying single, one may also consider the costs of relationship involvement, which single people have the advantage of avoiding. Prior research has shown that greater relationship conflict, hurt, and betrayal is associated with an increase in depression as well as poorer mental and physical health (Kiecolt-Glaser & Newton, 2001). Furthermore, poor quality relationships result in hurt feelings and anger (Lemay et al., 2012), and are more detrimental to well-being and health as compared to being single (Holt-Lunstad et al., 2008). It follows that simply being involved in a relationship does not guarantee psychological well-being.

Of particular relevance to the current work is whether individuals are satisfied with their relationship status (Lehmann et al., 2015). Satisfaction with one’s own relationship status may represent a bottom-up approach of choice, where the fulfilment of salient life domain goals (i.e., those who want to be partnered are partnered) result in positive influences on well-being (Oh et al., 2021). In a similar vein, we posited that examining the concept of one’s perceived readiness to enter a romantic relationship would highlight a better understanding of how relationship status may be associated with psychological well-being. To the extent that one’s feelings of “being ready” promote positive relationship-forming or relationship-maintaining attitudes and behaviours that strengthen a relationship and result in a greater fulfilling of one’s fundamental goals, commitment readiness may be another crucial piece of the puzzle to understand the extent to which single or coupled individuals experience enhanced or undermined psychological well-being.

2 Commitment Readiness: Amplifying Benefits and Costs of Relationship Involvement

Relationship receptivity theory (Agnew et al., 2019), in which the concept of commitment readiness is embedded, suggests that an individual’s subjective sense of timing plays a decisive role in motivating behaviours and cognitions toward relationship formation and maintenance. Receptiveness to enter a relationship to fulfil one’s need may vary based on both dispositional and situational factors that affect one’s openness to involvement in one (Hadden et al., 2018). For example, the emotional trauma associated with coming out of a recent breakup may discourage a particular individual from immediately looking for a new partner, while another individual may struggle with the anxiety associated with thoughts of remaining single in the future and hence be constantly on the lookout for a potential partner.

Across several domains, readiness has been identified to be a key component for initiating change and engaging in maintenance behaviours (e.g., Norcross et al., 2011). Particularly within the domain of romantic relationships, previous work has highlighted the positive association between readiness and behaviours that encourage relationship initiation (Hadden et al., 2018), where individuals who report a higher degree of readiness on one day engaged in more “pursuit” behaviours like flirting and physical touch, paired with increased interest in forming a relationship, the following day. People who entered relationships with higher readiness also expressed greater commitment to them. Moreover, higher readiness is linked to greater use of relationship maintenance strategies (Agnew et al., 2019), not only boasting an individual’s commitment to a relationship, but was also associated with the enactment of overt behaviours, such as less destructive responses to conflict. These findings suggest the potential of readiness to not only promote the formation of new relationships with greater initial commitment, but also to facilitate the strengthening of existing ones. Given the strong association between readiness and relationship-promoting behaviours, we would expect that individuals high in readiness would tend to act in a pro-relationship manner, entailing more fruitful and intimate interactions within their relationship. Additionally, considering the relative importance of seeking and forming close relationships with others in contributing to one’s psychological well-being (Erikson, 1968), it is expected that readiness would be associated with greater psychological well-being to the extent that these pro-relationship behaviours successfully facilitate the greater formation and maintenance of these meaningful relationships.

Although no prior research has examined the issue, it seems clear that if readiness motivates prospective relationship initiation as well as relationship maintenance behaviours and cognitions, we should expect readiness to moderate the effect of relationship status on psychological well-being. Given that a higher degree of readiness is associated with a stronger incentive for an individual to develop a relationship, paired with greater tendencies to engage in relationship-promoting behaviours, this should be linked to deeper, more fulfilling relationships that satisfy psychological needs to a greater extent. Therefore, we predict that higher levels of readiness would be associated with greater psychological well-being from being in a relationship, amplifying the benefits of relationship involvement. However, consider a person low in readiness who is currently in a romantic relationship. For example, this could be someone who is looking to prioritize personal growth but is in a relationship with their high school sweetheart and perceives social network pressure to continue in the relationship (Agnew, 2014). Conversely, such a person would have a lower incentive to maintain the relationship they find themselves in, and hence exert less effort to develop it further (Agnew et al., 2019). Furthermore, it is possible that they might feel “stuck” or nonvoluntarily dependent on their current partner in so far as they do not feel ready but are in a committed relationship, thereby amplifying the costs of relationship involvement (Tan et al., 2018). Hence, we predict that lower levels of readiness would be associated with lower psychological well-being for coupled individuals.

A single person high in readiness perceives that the “timing is right” and appropriate for them to become involved in a romantic relationship. They might desire a romantic partner (MacDonald & Park, 2022; Tan et al., 2020c) not be satisfied with being single (Lehmann et al., 2015), and thus evidence lower well-being as compared to their coupled counterparts. However, for single individuals who are low in readiness and do not think that the timing is currently “right” to be in a romantic relationship, not being involved in one provides the benefit of avoiding negative experiences that accompany poor quality relationships (or the prospect of poor-quality relationships), thereby reducing the costs of relationship involvement. In this situation, single individuals low in readiness should report higher levels of well-being than their coupled counterparts.

Importantly, prior research has shown strong positive effects between subjective socioeconomic status (SES) and well-being (Tan et al., 2020a). Beyond the main effect of SES, studies investigating the moderating effect of relationship status (i.e., single vs. married) showed that being married buffered against lower SES in terms of mortality (Choi & Marks, 2011; Smith & Waitzman, 1994) as well as mental health (Carlson & Kail, 2018). Beyond merely examining relationship status, research examining relationship quality also highlighted how partner commitment in close relationships can also buffer the effect of lower SES on well-being (Tan et al., 2020b). Essentially, to the extent that readiness amplifies the benefits and costs of relationship status, it is possible that relationship status X SES interaction might also be amplified by readiness. Hence, we conducted additional analyses controlling for subjective SES and also examined whether SES further moderates our hypothesized effects of relationship status X readiness on well-being.

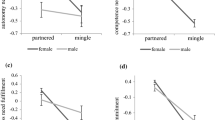

In summary, the present research aimed to assess how commitment readiness might moderate the association between individuals’ current relationship status and their psychological well-being. We hypothesized that readiness would be positively associated with psychological well-being (H1). We also hypothesized that readiness would moderate the effect of being single or coupled on psychological well-being (H2) (see Fig. 1). Specifically, we hypothesized that there would be a positive association between relationship involvement and well-being for those higher in readiness and a negative association between relationship involvement and well-being for those lower in readiness.

3 Study 1

Study 1 was designed to provide initial correlational evidence regarding the hypothesized moderating effects of readiness on the association between relationship status and psychological well-being using data obtained from a sample of undergraduate students. This and the subsequent studies were not preregistered, but all data and analytic code are available on the Open Science Framework (OSF): https://osf.io/fxa9y/?view_only=d8289fd579b94ba4b0cced8d89599ff3.

3.1 Method

3.1.1 Participants and Procedure

Seven-hundred and ninety-four young adults (185 men, 609 women; 364 currently coupled; Mage = 22.10, SD = 1.614) from a large public university in Singapore were recruited to complete an online survey and were remunerated SGD$5 for participation. To maximise power, we collected data from as many participants as possible throughout two semesters. Participants completed IRB-approved informed consent, answered questions regarding their relationship status and well-being as well as the commitment readiness scale and measures of perceived partner commitment amongst others. Finally, they answered demographic questions before being debriefed. Assuming a two-tailed test and an alpha of 0.05, sensitivity power analyses using G*Power (Faul et al., 2007) showed that this sample size provides 80% power to detect an effect of partial r2 = 0.009 and 60% power to detect an effect of partial r2 = 0.006 (Da Silva Frost & Ledgerwood, 2020), thus we had adequate power to detect hypothesized effects if present.

3.1.2 Measures

3.1.2.1 Relationship Status

Relationship status was assessed with a single self-report measure asking participants if they were currently in a committed romantic relationship (1 = Yes, 0 = No).

3.1.2.2 Psychological Well-being

Well-being was assessed with an 18-item scale that measures aspects such as autonomy, personal growth, and self-acceptance (Ryff & Keyes, 1995). Participants rated on a 7-point Likert scale (1 = Strongly Disagree, 7 = Strongly Agree) the extent to which they agreed with each item on the scale (e.g., “Some people wander aimlessly through life, but I am not one of them”, “In general, I feel I am in charge of the situation in which I live”; α = 0.84).

3.1.2.3 Commitment Readiness

Commitment readiness was assessed using an 8-item scale that measures the extent to which individuals are currently ready for a committed romantic relationship (Agnew et al., 2019), with participants rating on a 9-point Likert scale (0 = Strongly Disagree, 8 = Strongly Agree) the extent to which they agreed with each item (e.g., “I feel that this is the “right time” for me to be in a committed relationship”, “Now is not the time for me to be involved in a committed romantic relationship” [R]; α = 0.95).

3.1.2.4 Subjective SES

Subjective SES was assessed using the MacArthur scale of Subjective Social Status (Adler et al., 2000), a 1-item measure rated on a 10-point scale (0 = bottom rung, 10 = top rung) that assessed a person’s perceived rank relative to others in their group, in this case, Singapore.

3.2 Results

We report descriptive statistics and correlations among Study 1 variables in Table 1. We tested initially for a three-way interaction between participant-reported gender, relationship status and commitment readiness (in this and the subsequent two studies) and did not find any significant three-way interactions, so gender was not included further in model tests. Multiple regression was used to test for hypothesized main effects and the predicted two-way interaction between relationship status (0 = single, 1 = coupled) and mean-centered commitment readiness as predictors of well-being.

Consistent with H1, readiness was significantly and positively associated with psychological well-being [b = 0.069, t(790) = 3.938, p < .001, 95% Confidence Interval (CI) = 0.035, 0.103]. Consistent with past research, relationship status also significantly though modestly associated with well-being [b = − 0.135, t(790) = -2.078, p = .038, CI = − 0.262, − 0.007].

Consistent with H2, we found a significant two-way interaction between relationship status and commitment readiness [b = 0.155, t(790) = 4.627, p < .001, CI = 0.089, 0.220]. Simple slopes analysis at high (+ 1 SD) and low (− 1 SD) levels of readiness on well-being indicated that at low levels of readiness, there was a negative association between relationship status and well-being [b = − 0.451, t(790) = -4.154, p < .001, CI = − 0.664, − 0.238]. At high levels of readiness, there was a positive association between relationship status and well-being [b = 0.181, t(790) = 2.351, p = .019, CI = 0.030, 0.333]. That is, coupled individuals reported lower well-being compared to single individuals at low levels of readiness whereas it was the opposite at high levels of readiness (see Fig. 2).

Analysing simple slopes at different levels of relationship status showed a positive association between readiness and well-being when single [b = 0.069, t(790) = 3.938, p < .001, CI = 0.035, 0.103]. This association was significantly stronger for those currently involved in a romantic relationship [b = 0.224, t(790) = 7.862, p < .001, CI = 0.168, 0.279].

We tested whether this interaction effect would remain while controlling for subjective SES. The interaction remained significant [b = 0.151, t(790) = 4.586, p < .001, CI = 0.086, 0.215]. Finally, we also tested whether subjective SES would moderate the effects of relationship status x readiness on wellbeing. This three-way interaction was not significant [b = − 0.001, t(785) = -0.687, p = .945, CI = − 0.042, 0.039].

4 Study 2

Study 2 provided an opportunity to test the hypothesized moderating role of commitment readiness using data obtained from a community sample of individuals residing in Singapore. This sample helps to rectify the participant gender imbalance as well as the age and SES range restrictions in the Study 1 sample of undergraduate students. In addition to replicating our hypothesis tests, we again examined if our effects would hold when controlling for both gender and age, as well as whether gender and age would moderate the hypothesized effects, given prior research showing the effects of discrimination on well-being (Girme et al., 2022a) for older single adults (DePaulo & Morris, 2005) as well as for single women (Ji, 2015).

4.1 Method

4.1.1 Participants and Procedure

Four-hundred and forty adults (220 men, 220 women; 220 currently coupled; age M = 29.98, SD = 5.541) residing in Singapore were recruited via the Dynata Panel service. Once again, participants answered demographic questions about relationship status, SES, gender, and age as well as completing measures of well-being and commitment readiness before being debriefed. Sensitivity power analyses using G*Power (Faul et al., 2007) showed that this sample size provides 80% power to detect an effect of partial r2 = 0.018.

4.1.2 Measures

Relationship Status, Commitment Readiness (α = 0.87), Psychological Well-being (α = 0.81), and Subjective SES were assessed as described previously.

4.2 Results

We report descriptive statistics and correlations among Study 2 variables in Table 2. Following the identical analytic approach described in the previous study, consistent with H1, readiness significantly predicted psychological well-being, with higher levels of readiness associated with higher levels of psychological well-being [b = 0.094, t(433) = 3.521, p < .001, 95% CI = 0.041, 0.146]. Although significantly correlated, relationship status did not predict well-being when assessed as a main effect in the model [b = 0.115, t(433) = 0.115, p = .086].

Consistent with H2, there was also a significant two-way interaction between relationship status and commitment readiness [b = 0.119, t(433) = 2.990, p = .003; CI = 0.041, 0.197]. A simple slopes analysis of relationship status at high (+ 1 SD) and low (− 1 SD) levels of readiness showed that there was a positive association between relationship status and well-being at high levels of readiness [b = 0.315, t(433) = 3.403, p = .007, CI = 0.133, 0.497] whereas there was no significant effect at low levels of readiness [b = − 0.086, t(433) = -0.889, p = .374, CI = − 0.275, 0.104]. That is, coupled individuals reported lower well-being compared to single individuals at low levels of readiness whereas it was the opposite at high levels of readiness (see Fig. 3). Examining simple slopes at different levels of relationship status revealed that there was a positive association between readiness and well-being when single [b = 0.094, t(433) = 3.521, p < .001, CI = 0.041, 0.146], but this association was significantly stronger for those currently involved in romantic relationships [b = 0.213, t(433) = 7.18, p < .001, CI = 0.154, 0.271].

We tested whether this interaction effect would remain while controlling for age as well as subjective SES. The interaction remained significant [b = 0.174, t(433) = 4.384, p < .001, CI = 0.096, 0.252]. Finally, we also tested whether subjective SES would moderate the effects of relationship status x readiness on wellbeing. This three-way interaction was not significant [b = 0.027, t(427) = 1.293, p = .197, CI = − 0.014, 0.069].

5 Study 3

Studies examining relationship status and well-being are typically homogenous in nature, showcasing how cross-cultural comparisons are needed to establish the generalizability of our findings. This is especially important since prior research has highlighted cultural differences in the attitudes and perceptions surrounding one’s relationship status, particularly in terms of how “Eastern” cultures emphasize the importance of marriage and discriminate against singles compared to “Western” cultures (Himawan et al., 2018). Hence, Study 3 used data obtained from two countries, the United States and Singapore, to determine if the findings obtained in the first two studies replicate in different cultures. Specifically, the United States has typically been labelled as “Western”, and “Westerners” typically endorse independent self-construals, which is characterized by separation from others, primacy of personal goals and self-expression. On the other hand, Singapore being in Asia is typically labelled as “Eastern”, and “Easterners” typically endorse interdependent self-construals, which is characterized by valuing close connections to others, maintaining social norms and harmony, and the primacy of collective goals (Markus & Kitayama, 1991). This is corroborated by their individualism scores on Hofstede’s 6-D Model of National Culture, with USA scoring 91 and Singapore scoring 20 (Hofstede Insights, 2023). As such, singlehood might be viewed especially detrimentally in “Eastern” compared to “Western” cultures. Hence, it is possible that the effects of relationship status X commitment readiness on well-being might also be different for individuals from “Eastern” compared to “Western” cultures.

Furthermore, given the growing body of work attesting to the importance of desire for a relationship in predicting well-being among single people (e.g., Kislev, 2021; MacDonald & Park, 2022), we also tested whether our hypothesized interaction between relationship status and commitment readiness remained significant above and beyond one’s desire for a committed relationship.

5.1 Method

5.1.1 Participants and Procedure

Five-hundred and thirty-two adults (198 men, 329 women, 5 undisclosed; 268 currently coupled; age M = 28.96, SD = 5.897) residing in Singapore (n = 268) and the USA (n = 259) were recruited via the Qualtrics panel service (5 participants did not report their country). Participants completed informed consent as well as measures of commitment readiness, psychological well-being, and demographic questions such as their relationship status, gender, age, and subjective SES before being debriefed. Sensitivity power analyses using G*Power (Faul et al., 2007) showed that this sample provides 80% power to detect an effect of partial r2 = 0.015.

5.1.2 Measures

Relationship Status, Commitment Readiness (α = 0.89), Psychological Well-being (α = 0.79), and Subjective SES were assessed as described previously.

5.1.2.1 Commitment Desirability

Commitment desirability was assessed using a 5-item scale that measured the extent to which individuals desires a committed romantic relationship at the current point in time (Tan et al., 2020c) with participants rating on a 9-point Likert scale (0 = Strongly Disagree, 8 = Strongly Agree) the extent to which they agreed with each item (e.g., “I want to be in a committed relationship”, “Maintaining a committed romantic relationship is important to me”; α = 0.88).

5.2 Results

We report descriptive statistics and correlations among Study 3 variables in Table 3. Following the identical analytic approach described in the previous studies, consistent with H1, readiness significantly predicted psychological well-being, with higher levels of readiness associated with higher levels of psychological well-being [b = 0.074, t(528) = 2.968, p = .003, 95% CI = 0.025, 0.123]. Once again, although modestly correlated, relationship status did not significantly predict well-being when assessed as a main effect [b = − 0.077, t(528) = -1.124, p = .261, CI = − 0.210, 0.057].

Consistent with H2, there was a significant two-way interaction between relationship status and commitment readiness [b = 0.148, t(528) = 4.113, p < .001; CI = 0.077, 0.219]. A simple slopes analysis of relationship status at high (+ 1 SD) and low (− 1 SD) levels of readiness showed that there was a positive association between relationship status and well-being at high levels of readiness [b = 0.204, t(528) = 2.135, p = .033, CI = 0.016, 0.391], whereas there was also a negative effect at low levels of readiness [b = − 0.357, t(528) = -3.674, p = .003, CI = − 0.547, − 0.166]. Specifically, coupled individuals reported lower well-being compared to single individuals at low levels of readiness whereas it was the opposite at high levels of readiness (see Fig. 4). Examining simple slopes at different levels of relationship status revealed that there was a positive association between readiness and well-being when single [b = 0.074, t(528) = 2.968, p = .003, CI = 0.025, 0.123], but this association was significantly stronger for those currently involved in romantic relationships [b = 0.222, t(528) = 8.519, p < .001, CI = 0.171, 0.273].

Again, we tested whether this interaction effect would remain while controlling for age as well as subjective SES; it remained significant [b = 0.166, t(526) = 4.684, p < .001, CI = 0.096, 0.236]. Furthermore, we tested whether culture/country of residence (0 = Singapore, 1 = USA) moderated the effects of relationship status X readiness on wellbeing. There was no significant three-way interaction [b = − 0.096, t(519) = -1.321, p = .187, CI = − 0.238, 0.047].

Finally, we tested whether our hypothesized moderation of relationship status X readiness on wellbeing would remain significant when controlling for commitment desirability as well as the relationship status X desirability interaction. Our hypothesized moderation of relationship status X readiness remained significant [b = − 0.155, t(526) = 3.065, p = .002, CI = 0.056, 0.255]. There was no main effect of desirability [b = 0.038, t(526) = 1.433, p = .153, CI = − 0.014, 0.090] nor any effect of relationship status X desirability [b = − 0.016, t(526) = − 0.324, p = .746, CI = − 0.113, 0.081] on well-being.

5.3 Integrative Data Analysis

Our hypothesized interaction between relationship status and commitment readiness was found to be largely consistent across the three studies. Nonetheless, we also conducted an integrative data analysis (IDA; Curran & Hussong, 2009), a statistical aggregation approach used with multiple datasets to showcase an overall assessment of study hypotheses across samples. As preparation for the IDA, readiness was standardized across samples. Results from the IDA indicated that the two-way interaction between relationship status and commitment readiness was robust [b = 0.246, t(1757) = 6.358, p < .001; CI = 0.170, 0.322]. A simple slopes analysis of relationship status at high (+ 1 SD) and low (− 1 SD) levels of readiness showed that there was a positive association between relationship status and well-being at high levels of readiness [b = 0.207, t(1757) = 4.082, p < .001, CI = 0.108, 0.307], whereas there was also a negative effect at low levels of readiness [b = − 0.285, t(1757) = -4.948, p < .001, CI = − 0.398, − 0.172]. Again, coupled individuals reported lower well-being compared to single individuals at low levels of readiness whereas it was the opposite at high levels of readiness (see Fig. 5). Similarly, examining simple slopes at different levels of relationship status revealed that there was a positive association between readiness and well-being when single [b = 0.147, t(1757) = 6.020, p < .001, CI = 0.099, 0.195], but this association was significantly stronger for those currently involved in romantic relationships [b = 0.393, t(1757) = 13.032, p < .001, CI = 0.334, 0.452].

6 General Discussion

Findings from three independent samples of participants (two from Singapore, one cross-cultural comparison between Singapore and USA) provided strong evidence supporting how commitment readiness amplified the benefits and costs of romantic relationship involvement. Readiness was significantly positively associated with psychological well-being. More importantly, results revealed a significant interaction between readiness and relationship status. At higher levels of commitment readiness, individuals reported greater well-being if they were in a relationship, as compared to individuals who were not coupled. In contrast, at lower levels of readiness, individuals reported lower well-being if they were in a romantic relationship, as compared to individuals who were not in one. These results highlight the importance of commitment readiness as a significant moderator, adding to recent research challenging conventional wisdom that simply being involved in a romantic relationship is beneficial for well-being.

Furthermore, our hypothesized interaction held controlling for potential covariates such as gender, age, and SES. There were no gender or age main effects on well-being, but there was a significant positive main effect of subjective SES on well-being. Although it was initially posited that readiness could possibly amplify the effects of relationship status X SES on well-being, we found no such effect. Given that our hypothesized interaction between relationship status X readiness held controlling for SES, we are more confident regarding the validity of commitment readiness as an important moderator in amplifying the benefits and costs of being coupled. Furthermore, recent research has also found that lack of social support and discrimination contribute to single individuals’ reports of lower well-being compared to coupled individuals (DePaulo & Morris, 2005; Girme et al., 2022a; Gordon et al., 2016; Stronge et al., 2019). Hence, it could be possible that the moderating effect of readiness might be different based on gender, age as well. However, these covariates did not further moderate the interaction between relationship status and commitment readiness on well-being. Thus, it was not the case that only a subset of single or coupled individuals reported different levels of well-being as a function of readiness, which highlights how the subjective sense of readiness might be a relatively homogenous experience for single and coupled individuals. Nonetheless, being mindful of diverse singlehood or coupled experiences remains important for future research (e.g., Girme et al., 2022b).

We see individuals who are low in readiness but find themselves in committed romantic relationships as a particularly interesting group to consider. As mentioned, these could be individuals who are looking to prioritize personal goal pursuits over relationship involvement, but nonetheless find themselves already in a committed relationship that they may now feel “stuck in” (Agnew et al., 2019; Tan et al., 2018). Indeed, we found that coupled individuals who felt less ready reported lower well-being. Given the IDA showed evidence for a negative association between relationship status and well-being at low levels of readiness, future research could examine if relationship quality attenuates the negative association between readiness and well-being for those who are currently involved in relationships.

It is also interesting to note the prevailing main effect of readiness on well-being across all three studies, where even single people who felt more ready for relationships, despite not currently being involved in one, consistently reported higher levels of well-being. With reference to previous work on relationship status satisfaction (Lehmann et al., 2015) and relationship desire (Kislev, 2021), one might initially expect that a mismatch between an individual’s readiness for a relationship and actual relationship status (i.e., being ready for a relationship but not being able to find a romantic partner) would result in lower well-being. Future research should examine whether readiness when being single or partnered is associated with one’s satisfaction with the status quo in terms of voluntary and involuntary singlehood (Lehmann et al., 2015) and whether it may serve to mediate the interaction effect of relationship status and commitment readiness on well-being. Feeling particularly ready for a relationship could be an indication that an individual’s current needs are being fulfilled and that they are primed for a relationship opportunity should one arise. From this, we can appreciate the robust effect of readiness on well-being, boasting commitment readiness as a new and potentially important construct when considering well-being.

6.1 Limitations and Future Directions

The current research has several limitations that we wish to raise. First, the data presented in our current studies are correlational in nature. It could be possible that well-being influences readiness instead of our hypothesized direction (although exploratory analyses did not find an interaction between relationship status and well-being on readiness), and future research could attempt to manipulate readiness to establish clear causality. Beyond understanding causality, a focus on the longitudinal course of readiness on well-being would be valuable. For example, there might be differential effects for someone who is ready for a relationship but has been unpartnered for a long period of time as compared to one who is unpartnered only for a short while. Tracking the developmental trajectory of single/partnered individuals and how they wax and wane with respect to readiness and well-being would provide a valuable descriptive account of within-person effects of relationship transitions (or non-transitions) as well as information regarding whether there are bi-directional/cross-lagged associations between readiness and well-being (e.g., Oh et al., 2021). This could serve to uncover underlying pathways explaining the association between readiness and well-being.

Another limitation of the current study was that we did not measure perceptions of social support availability in our current samples. As previously mentioned, recent research has found that the lack of social support contributes to single individuals’ reports of lower well-being compared to coupled individuals (Girme et al., 2022a). It is possible that for those who are high in readiness, the lack of social support availability is especially salient for single vs. coupled individuals, whereas for those who are low in readiness, the lack of social support availability becomes especially salient for coupled vs. single individuals. Hence, perceived social support could be a potential mediator for the moderation between relationship status and commitment readiness on well-being.

The current research also boasts several strengths. This set of studies represents the first attempt to investigate empirically the moderating role of commitment readiness and how it might be associated with well-being for single vs. coupled individuals. The moderation results replicated across three samples in three different contexts, including a sample of undergraduate students among whom being single is normative (Study 1), in a sample of adults controlling for SES and age (Study 2), and with participants from different national settings (Study 3). Moreover, the current investigation is one of few to investigate how individual differences can moderate the link between relationship status and well-being, such as approach/avoidance goals (Girme et al., 2016) or attachment (MacDonald & Park, 2022). Furthermore, we included data from samples that are not Western, and beyond “WEIRD” in nature (Henrich et al., 2010). However, we should take note that individuals from Singapore are still typically educated, industrialized and rich (E, I, and R). As such, one could look to collect samples from other countries that represent greater cultural diversity for greater confidence in the generalizability of our results. These initial findings suggest the importance of considering the functions of readiness within the context of close relationships and we encourage future investigations in this area.

Data Availability

The current research was not preregistered. All data, materials and syntax can be found at https://osf.io/fxa9y/?view_only=d8289fd579b94ba4b0cced8d89599ff3.

References

Adamczyk, K., & Segrin, C. (2015). Direct and indirect effects of young adults’ relationship status on life satisfaction through loneliness and perceived social support. Psychologica Belgica, 55(4), 196–211. https://doi.org/10.5334/pb.bn

Adler, N. E., Epel, E. S., Castellazzo, G., & Ickovics, J. R. (2000). Relationship of subjective and objective social status with psychological and physiological functioning: Preliminary data in healthy white women. Health Psychology, 19, 586–592. https://doi.org/10.1037/0278-6133.19.6.586

Agnew, C. R. (Ed.). (2014). Social influences on romantic relationships: Beyond the dyad. Cambridge University Press.

Agnew, C. R., Hadden, B. W., & Tan, K. (2019). It’s about time: Readiness, commitment, and stability in close relationships. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 10, 1046–1055. https://doi.org/10.1177/1948550619829060

Baumeister, R. F., & Leary, M. R. (1995). The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychological Bulletin, 117, 497–529. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.117.3.497

Böger, A., & Huxhold, O. (2020). The changing relationship between partnership status and loneliness: Effects related to aging and historical time. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences & Social Sciences, 75, 1423–1432. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gby153

Carlson, D. L., & Kail, B. L. (2018). Socioeconomic variation in the association of marriage with depressive symptoms. Social Science Research, 71, 85–97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssresearch.2017.12.008

Choi, H., & Marks, N. F. (2011). Socioeconomic status, Marital Status Continuity and Change, Marital Conflict, and Mortality. Journal of Aging and Health, 23(4), 714–742. https://doi.org/10.1177/0898264310393339

Chopik, W. J. (2017). Associations among relational values, support, health, and well-being across the adult lifespan. Personal Relationships, 24, 408–422. https://doi.org/10.1111/pere.12187

Cohen, S. (2004). Social relationships and health. American Psychologist, 59, 676–684. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.59.8.676

Conley, T. D., Ziegler, A., Moors, A. C., Matsick, J. L., & Valentine, B. (2013). A critical examination of popular assumptions about the benefits and outcomes of monogamous relationships. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 17, 124–141. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088868312467087

Curran, P. J., & Hussong, A. M. (2009). Integrative data analysis: The simultaneous analysis of multiple data sets. Psychological Methods, 14, 81–100. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0015914

da Silva Frost, A., & Ledgerwood, A. (2020). Calibrate your confidence in research findings: A tutorial on improving research methods and practices. Journal of Pacific Rim Psychology, 14, https://doi.org/10.1017/prp.2020.7

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2000). The what and why of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychological Inquiry, 11, 227–268. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327965PLI1104_01

DePaulo, B. M., & Morris, W. L. (2005). Singles in society and in science. Psychological Inquiry, 16, 57–83. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327965pli162&3_01

Diener, E., Suh, E. M., Lucas, R. E., & Smith, H. L. (1999). Subjective well-being: Three decades of progress. Psychological Bulletin, 125, 276–302. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.125.2.276

Dush, C. M. K., & Amato, P. R. (2005). Consequences of relationship status and quality for subjective well-being. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 22, 607–627. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407505056438

Erikson, E. H. (1963). Childhood and society (2nd ed.). Norton.

Erikson, E. H. (1968). Identity: Youth and crisis. WW Norton.

Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Lang, A. G., & Buchner, A. (2007). G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behavior Research Methods, 39, 175–191. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03193146

Gable, S. L., Reis, H. T., Impett, E. A., & Asher, E. R. (2004). What do you do when things go right? The intrapersonal and interpersonal benefits of sharing positive events. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 87, 228. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.87.2.228

Girme, Y. U., Overall, N. C., Faingataa, S., & Sibley, C. G. (2016). Happily single: The link between relationship status and well-being depends on avoidance and approach social goals. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 7, 122–130. https://doi.org/10.1177/1948550615599828

Girme, Y. U., Park, Y., & MacDonald, G. (2022b). Coping or Thriving? Reviewing Intrapersonal, Interpersonal, and Societal Factors Associated With Well-Being in Singlehood From a Within-Group Perspective. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 0(0). https://doi.org/10.1177/17456916221136119

Girme, Y. U., Sibley, C. G., Hadden, B. W., Schmitt, M. T., & Hunger, J. M. (2022a). Unsupported and stigmatized? The association between relationship status and well-being is mediated by social support and social discrimination. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 13(2), 425–435. https://doi.org/10.1177/19485506211030102

Gordon, T. (2016). Single women: On the margins? Macmillan International Higher Education.

Hadden, B. W., Agnew, C. R., & Tan, K. (2018). Commitment readiness and relationship formation. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 44, 1242–1257. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167218764668

Haring-Hidore, M., Stock, W. A., Okun, M. A., & Witter, R. A. (1985). Marital status and subjective well-being: A research synthesis. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 47, 947–953. https://doi.org/10.2307/352338

Henrich, J., Heine, S., & Norenzayan, A. (2010). Most people are not WEIRD. Nature, 466, 29. https://doi.org/10.1038/466029a

Himawan, K. K., Bambling, M., & Edirippulige, S. (2017). Modernization and singlehood in Indonesia: Psychological and social impacts. Kasetsart Journal of Social Sciences, 40(2), 499–506. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.kjss.2017.09.008

Himawan, K. K., Bambling, M., & Edirippulige, S. (2018). The asian single profiles: Discovering many faces of never married adults in Asia. Journal of Family Issues, 39, 3667–3689. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X18789205

Hofstede Insights (2023, May 10). Country comparison tool Hofstede-Insights. https://www.hofstede-insights.com/country-comparison-tool

Holt-Lunstad, J., Birmingham, W., & Jones, B. Q. (2008). Is there something unique about marriage? The relative impact of marital status, relationship quality, and network social support on ambulatory blood pressure and mental health. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 35(2), 239–244. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12160-008-9018-y

Holt-Lunstad, J., Smith, T. B., Baker, M., Harris, T., & Stephenson, D. (2015). Loneliness and social isolation as risk factors for mortality: A meta-analytic review. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 10, 227–237. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691614568352

Ji, Y. (2015). Between tradition and modernity: Leftover women in Shanghai. Journal of Marriage and Family, 77, 1057–1073.

Jones, G. W., & Yeung, W. J. J. (2014). Marriage in Asia. Journal of Family Issues, 35(12), 1567–1583. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X14538029

Kiecolt-Glaser, J. K., & Newton, T. L. (2001). Marriage and health: His and hers. Psychological Bulletin, 127, 472–503. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.127.4.472

Kislev, E. (2021). Reduced relationship desire is associated with better life satisfaction for singles in Germany: An analysis of pairfam data. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 38, 2073–2083. https://doi.org/10.1177/02654075211005024

Lazarus, R. S., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, appraisal, and coping. Springer publishing company.

Lehmann, V., Tuinman, M. A., Braeken, J., Vingerhoets, A. J., SanDerman, R., & Hagedoorn, M. (2015). Satisfaction with relationship status: Development of a new scale and the role in predicting well-being. Journal of Happiness Studies, 16, 169–184. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-014-9503-x

Lemay, E. P. Jr., Overall, N. C., & Clark, M. S. (2012). Experiences and interpersonal consequences of hurt feelings and anger. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 103, 982–1006. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0030064

Lucas, R. E., & Dyrenforth, P. S. (2005). The myth of marital bliss? Psychological Inquiry, 16, 111–115. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20447271

MacDonald, G., & Park, Y. (2022). Associations of attachment avoidance and anxiety with life satisfaction, satisfaction with singlehood, and desire for a romantic partner. Personal Relationships, 29, 163–176. https://doi.org/10.1111/pere.12416

Maree, J. G. (2021). The psychosocial development theory of Erik Erikson: Critical overview. Early Child Development and Care, 191(7–8), 1107–1121. https://doi.org/10.1080/03004430.2020.1845163

Markus, H. R., & Kitayama, S. (1991). Culture and the self: Implications for cognition, emotion, and motivation. Psychological Review, 98(2), 224–253. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.98.2.224

McPherson, C. J., Wilson, K. G., & Murray, M. A. (2007). Feeling like a burden: Exploring the perspectives of patients at the end of life. Social Science & Medicine, 64(2), 417–427. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.09.013

Milan, A. (2013). Marital status: Overview, 2011. Component of Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 91-209-X. Statistics Canada. Minister of Industry. Retrieved from http://www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/91-209-x/2013001/article/11788-eng.pdf

Norcross, J. C., Krebs, P. M., & Prochaska, J. O. (2011). Stages of change. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 67, 143–154. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.20758

Oh, J., Chopik, W. J., & Lucas, R. E. (2021). Happiness singled out: Bidirectional associations between singlehood and life satisfaction. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 0(0), https://doi.org/10.1177/01461672211049049

Purol, M. F., Keller, V. N., Oh, J., Chopik, W. J., & Lucas, R. E. (2021). Loved and lost or never loved at all? Lifelong marital histories and their links with subjective well-being. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 16, 651–659. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2020.1791946

Reis, H. T., Collins, W. A., & Berscheid, E. (2000). The relationship context of human behavior and development. Psychological Bulletin, 126(6), 844–872. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.126.6.844

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2001). On happiness and human potentials: A review of research on hedonic and eudaimonic well-being. Annual Review of Psychology, 52, 141–166.

Ryff, C. D., & Keyes, C. L. M. (1995). The structure of psychological well-being revisited. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 69(4), 719–727. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.141

Simpson, R. (2016). Singleness and self-identity: The significance of partnership status in the narratives of never-married women. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 33(3), 385–400. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407515611884

Smith, K. R., & Waitzman, N. J. (1994). Double Jeopardy: Interaction effects of marital and poverty status on the risk of mortality. Demography, 31, 487–507. https://doi.org/10.2307/2061754

Soons, J. P. M., & Liefbroer, A. C. (2008). Together is better? Effects of relationship status and resources on young adults’ well-being. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 25, 603–624. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407508093789

Stronge, S., Overall, N. C., & Sibley, C. G. (2019). Gender differences in the associations between relationship status, social support, and wellbeing. Journal of Family Psychology, 33, 819–829. https://doi.org/10.1037/fam0000540

Tan, J. J. X., Kraus, M. W., Carpenter, N. C., & Adler, N. E. (2020a). The association between objective and subjective socioeconomic status and subjective well-being: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 146, 970–1020. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000258

Tan, J. J. X., Kraus, M. W., Impett, E. A., & Keltner, D. (2020b). Partner commitment in close relationships mitigates social class differences in subjective well-being. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 11(1), 16–25. https://doi.org/10.1177/1948550619837006

Tan, K., Agnew, C. R., & Hadden, B. W. (2020c). Seeking and ensuring interdependence: Desiring commitment and the strategic initiation and maintenance of close relationships. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 46, 36–50. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167219841633

Tan, K., Arriaga, X. B., & Agnew, C. R. (2018). Running on empty: Measuring psychological dependence in close relationships lacking satisfaction. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 35, 977–998. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407517702010

Tan, K., & Tay, L. (2022). Relationships and well-being. In R. Biswas-Diener & E. Diener (Eds), Noba textbook series: Psychology. Champaign, IL: DEF publishers. Retrieved from http://noba.to/h2tu6sxn

Funding

Preparation of this manuscript was supported in part by an Academic Research Fund (AcRF) Tier 1 grant from the Singapore Ministry of Education (MOE).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Research Involving Human Participants Statement

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the SMU Institutional Review Board and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tan, K., Ho, D. & Agnew, C.R. Relationship Status and Psychological Well-being: Initial Evidence for the Moderating Effects of Commitment Readiness. J Happiness Stud 24, 2563–2581 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-023-00692-w

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-023-00692-w